Are bird flu and measles genuine threats or just another round of manufactured panic?

Listen to the audio version of this article:

THE TOPLINE

- Public health emergencies often serve to justify policy shifts that concentrate authority and favor pharmaceutical solutions over broader systemic health approaches.

- The framing of these diseases focuses on fear and compliance rather than a balanced discussion of immune resilience, nutrition, and alternative public health strategies.

In an era where crises seem to emerge in an endless cycle, the latest alarms over measles outbreaks in rural Texas and the looming specter of H5N1 bird flu expose a deeper pattern—one in which fear becomes a tool for shaping public perception and behavior, justifying policy shifts, and concentrating power. The question is not merely whether these health threats are as severe as we’re led to believe, but why the response remains so predictably narrow, favoring centrally-controlled pharmaceutical interventions over holistic, region-specific, systems-based solutions.

Measles

With 159 reported cases reported so far in Texas, measles has returned to the national conversation. The prevailing media angle focuses on vaccine hesitancy and places blame on figures like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now the HHS Secretary, for questioning vaccine policies. We’re told that the unvaccinated are the problem, even though outbreaks have occurred in populations with over 95% vaccine coverage. The death of an unvaccinated child, attributed to measles by the Texas Department of Health, has added fuel to the fire, with the media predictably using the opportunity to scold anyone who may choose a health route other than one devised by the medico-industrial complex.

Once considered a routine childhood illness that conferred lifelong immunity and could be managed at the community level through ‘measles parties’, measles has been rebranded as a dire public health threat. The practice of measles parties, by contrast, is now regarded as “foolishness” and “dangerous.” While it is true that serious complications disproportionately affect individuals with poor nutrition and weakened immune systems, public discourse rarely centers on these factors. Instead of promoting immune support strategies, health authorities default to mass vaccination as the primary, and often sole, solution. Indeed, the health establishment gets angry at the mere suggestion of holistic solutions even if they are mentioned as an adjunct to vaccination.

This has been evident in the backlash to Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s March 3 written statement regarding the Texas outbreak. Near the top of the statement, RFK as HHS Secretary writes, in bold text: “Vaccines not only protect individual children from measles, but also contribute to community immunity, protecting those who are unable to be vaccinated due to medical reasons.” He then dares to state, “Parents play a pivotal role in safeguarding their children’s health. All parents should consult with their healthcare providers to understand their options to get the MMR vaccine. The decision to vaccinate is a personal one.” The nerve!

He goes on to remind us that, while vaccines have helped, “[by] 1960 — before the vaccine’s introduction — improvements in sanitation and nutrition had eliminated 98% of measles deaths. Good nutrition remains a best defense against most chronic and infectious illnesses. Vitamins A, C, and D, and foods rich in vitamins B12, C, and E should be part of a balanced diet.”

This, in our view, is exactly the kind of open-mindedness and embrace of holistic solutions we need from public health officials, an approach which was so glaringly absent during the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s no wonder trust in public health institutions has fallen to rock bottom!

Bird Flu and the Expansion of Centralized Authority

The H5N1 bird flu narrative follows a similar trajectory. The federal government’s One Health framework consolidates public health authority across multiple agencies, ostensibly to protect human, animal, and environmental health. While coordination is necessary in managing zoonotic diseases, this approach also raises questions about how centralized control impacts food systems, disease surveillance, and individual medical choice.

Simultaneously, the Department of Health and Human Services is reconsidering a nearly $600 billion contract with Moderna to develop an mRNA bird flu vaccine. Once again, the public health establishment has gone to bat for big pharma, arguing that the move jeopardizes our ability to respond to a health crisis. But the question remains: why must taxpayers pay hundreds of billions to Moderna to run trials on a vaccine that the company will then profit from? Why can’t Moderna raise its own capital from investors, and why don’t we get to choose to diversify our investment in solutions other than a vaccine?

The implicit message: preparedness requires preemptive pharmaceutical solutions, despite the lack of public discourse on alternative strategies.

Rethinking Investment in Public Health

A truly robust public health strategy would extend way beyond vaccination campaigns. Key areas of investment should include:

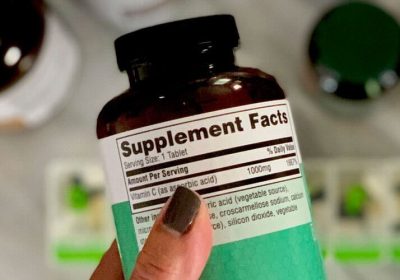

- Strengthening innate immunity through proper nutrition, supplementation, lifestyle modifications and public health education that empowers individuals to make informed health choices.

- Reevaluating biosafety lab procedures to ensure that human interventions in viral research do not inadvertently increase risks to human health.

- Encouraging non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as improved sanitation and nasal hygiene (which has been shown to reduce sick days by 20%).

- Building public trust through transparency, ensuring that health policies are informed by a balanced evaluation of risks and benefits rather than industry-driven imperatives.

Who Benefits from Back-to-Back Crises?

The recurring pattern of crisis-driven policymaking raises a critical question: who stands to gain most? When media narratives push fear over context, when government interventions default to coercive measures, and when pharmaceutical companies secure billions in emergency funding, the broader societal costs become clear.

If we are to move beyond one-size-fits-all public health and medicine, we must demand a more thoughtful approach—one that prioritizes resilience, decentralization, and informed choice. Fear should not be the foundation of public health policy. Instead, we need a framework that acknowledges complexity, fosters trust, and invests in long-term well-being rather than perpetual crisis management.

Please share this widely with your networks.

Before the vaccine, mothers transmitted antibodies aginst measles to their infants in breast milk. Babies were nursed up to a year. After the vaccine, when mothers had no longer been naturally immunized in childhood by catching the disease, they could no longer transmit antibodies, because the vaccine does not provide that kind of immunity to the mothers. Hence, infants were in greater danger, necessitating more vaccines.

I personally had rubella once and rubeola three times, thus enabling me to not only have lifetime immunity myself, but also protect my babies.

Ok. I’m vehemently opposed to vaccines. I have never been vaccinated nor have my children or grandchildren. I do understand that there will be people who contract diseases vaccinated or not. This being the case, it puts RFK Jr. in a difficult almost no win situation. I would, in an effort to be fair to all and allow freedom in this decision, give pharmaceutical company the money but only as a loan. As soon as the product hits the market, the pharmaceutical company has to start paying the money back. In no way should taxpayers have to fund research that ultimately puts money in the pharmaceutical pockets.

Let the bullshit begin. vaccines SAVE LIVES. Shame on you for suggesting otherwise!!!

Measles parties don’t happen anymore for 2 reasons.

1. They’re dangerous! Why would you risk the lives of your children just because you are angry with someone or some group? How devastated is that parent in Texas do you think?

2. With vaccines the occurrences of the measles were reduced so dramatically they became pointless. It was mute.

The only fear being pushed is by the Trump administration. The media is highlighting the faults in the actions and policies of this administration. RFKJ IS NOT A LICENSED MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL He has NO TRAINING. You may as well ask Siri or Alexa.

Better articles regarding RFK JR…

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0mzk2y41zvo.amp

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.cbsnews.com/amp/philadelphia/news/philadelphia-rfk-jr-confirmation-health-vaccines/

How many of these measles infections are in children of unvaccinated immigrants who are very numerous in the southwest. For some reason this factor is never mentioned politically incorrect I suppose but surely it’s a factor when millions have entered with no health checks, no health insurance etc. I don’t think unvaccinated American citizens are the majority of the problem since the majority are already vaccinated. I am adamantly opposed to more mRNA vaccines and the rest should be cleaned up and rid of the toxic ingredients.