Powerful forces are working to reshape and disrupt traditional food production, ushering in a new era of genetically engineered, lab-grown foods. As this transformation accelerates, will consumers be left in the dark about what they’re eating—and how it’s made? Action Alert!

Listen to the audio version of this article:

THE TOPLINE

- Synthetic biology (synbio) foods, including lab-grown dairy and meat made via precision fermentation, are being marketed as sustainable innovations but may undermine natural food systems, pose safety risks, and lack nutritional equivalence to real food.

- Despite never having been part of human diet, these products face minimal regulatory oversight in the US, making it hard for consumers to identify or avoid them.

- Independent analyses and lawsuits reveal concerning contaminants and nutritional deficiencies in synbio products, highlighting the urgent need for transparency, rigorous regulation, and public awareness.

Imagine pouring a glass of milk that never came from a cow. No sunlit pasture, no soil—just a sterile vat in a lab where genetically modified microbes churn out something that vaguely resembles the thing that cows emit from their udders yet still carries the same name.

Now imagine a future where most of your food is made this way.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s already happening. And it’s being sold to us as the future of food: efficient, sustainable, animal-free, climate-friendly, and high-tech.

At its core, this new food frontier seeks to replace living, interdependent systems with engineered components optimized for control and profit. It’s a vision we’re told that is driven by a desire for “precision”—but in isolating parts from the whole, it risks ignoring the complexity and wisdom of nature itself. In chasing innovation, we may be trading nourishment for novelty—and losing sight of what real food is.

In fact, “precision” is becoming the new prefix for all sorts of new technologies that leverage genomic technologies, patents, and business models, most of them sold with massive promises and little evidence, as yet, of either safety or effectiveness. “Precision” is the new industry catchword that avoids any mention of “genes” or “genetic modification” that have negative connotations among the public. Some common examples of the use of the prefix for new technological advancements include: precision agriculture, precision medicine, and precision fermentation, but there’s also precision nutrition, precision public health, precision diagnostics, precision livestock farming, precision forensics, precision neurotherapeutics, and precision drug discovery.

Precision is an attractive notion. But holism better represents how nature works. It emphasizes the idea that all parts of a system—whether it’s an organ in the human body, a crop or animal on a farm, or even a whole ecosystem—are inseparable from the bigger system—the whole—within which these sub-systems exist. You can’t understand or heal one part without understanding its place in the larger web. Precision, by contrast, isolates and tweaks, ignoring what the consequences might be on the interconnected whole. That’s exactly why the vast majority of drugs, with their specific and precise modes of action that interfere with or block specific pathways, have been so unsuccessful at remedying the plethora of chronic diseases that now threaten the very function of our society.

“Precision” fermentation and lab-grown foods are being marketed as the sustainable future of food, while in reality they may be leading us further away from real nourishment—and into a food system that’s synthetic, fragile, and dangerously out of sync with nature.

Lab-Grown Food: Innovation or Illusion?

Precision fermentation involves genetically engineered microbes that produce copies of ingredients typically derived from animals or plants. These ingredients are showing up in everything from “milk” to meat alternatives. And it’s not just startups doing this—global giants like Nestlé and Danone are also getting in on the action.

Despite the cutting-edge technology and patents behind these foods, US regulatory agencies have bought into the idea that they should be treated no differently than traditional foods. Shockingly, most of these products face little or no independent safety review before hitting grocery store shelves.

Disruption by Design

Tech leaders and investors like Bill Gates aren’t looking to provide just another food option at the grocery store; they’re looking to replace real food altogether. In Gates’ own words: “All rich countries should move to 100% synthetic beef.”

The dairy industry, in particular, is seen as ripe for disruption due to the relatively low protein content of milk at just about 3%, making it an easier product for precision fermentation to replicate. Who needs cows when you can “grow” milk with genetically engineered yeasts (fungi) or bacteria? Industry proselytizers argue this biosynthetic milk is so disruptive it could collapse the traditional dairy industry, especially given the latter’s dependency on subsidies and thin profit margins.

The Hype Meets Harsh Reality

The market for precision fermentation is indeed booming—valued at $3.2 billion in 2024 and projected to surpass $100 billion by 2034. Investment in synbio foods has already outpaced investment in plant-based meats. Yet, serious hurdles remain.

Startups in the space have seen funding dry up—down 70% in 2022 alone. High production costs and limited manufacturing capacity continue to plague the industry. For example, Bored Cow’s synbio milk currently sells for three to four times the price of organic dairy. While the cost of a lab-grown burger has dropped significantly from its original $300,000 price tag, it’s still around $20—far from competitive with conventional options.

Despite these challenges, major food industry players are moving in. Nestlé now uses precision fermentation to create a product called “Better Whey,” while companies like Fonterra, Leprino Foods, and Danone are exploring synbio ingredients for a variety of applications.

Consumers in the Dark

Savvy shoppers may be able to easily avoid products like Bored Cow, but the reality is that synbio ingredients are infiltrating more and more foods, and it will be difficult to know which ones. Perfect Day, the company behind Bored Cow, sells some of its synbio whey protein to other businesses like Mars and General Mills for use in their foods (though some of these products have been discontinued or dropped). It doesn’t seem as if regulators are going to require these foods be labeled as genetically modified or “bioengineered,” either, making it even more difficult for health-conscious consumers to ensure they avoid foods using these synbio ingredients.

Regulatory Blind Spots

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of this food revolution is its lack of meaningful oversight. In the US, synbio foods can be marketed through the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) pathway. As we explained with the release of our recent white paper, companies can affirm GRAS status by themselves without notifying the FDA, though several synbio food companies have sent their GRAS notices to the FDA and received a “no questions” letter, which is tacit approval of the product.

By contrast, in Europe, synbio foods must go through novel foods registration, which is a lengthier review process that is more appropriate to foods that have never been part of the human diet before.

As we’ve reported before, the government focuses solely on the final product, disregarding the novel methods used to create it. A tomato made via synthetic biology is treated the same as a farm-grown one, with no additional testing or labeling, because it is mistakenly viewed as “bioequivalent.” Meanwhile, in the European Union there remains a requirement for a far more rigorous novel foods review process, although there is an active discussion by Big Biotech protagonists that plants, animals, or products derived from either using precision breeding techniques (a subset of modern bioengineering) should not be subject to the stringent GMO regulations if these techniques result in traits that could have arisen through traditional breeding or cultivation.

It’s crucial to fight for meaningful regulatory review in light of what some of the science has uncovered lurking in synbio foods.

What’s Really in These Foods?

Independent studies have cast serious doubt on the safety and bioequivalence of synbio foods. A recent lawsuit by the Organic Consumers Association and Toxin Free USA against Perfect Day, a leader in precision-fermented dairy, revealed troubling findings. According to the suit, Perfect Day’s ProFerm whey protein contains fungal contaminants in quantities seven times greater than the actual whey protein. Testing uncovered 93 different fungal compounds, none of which have a history of human consumption, and whose health effects remain unknown.

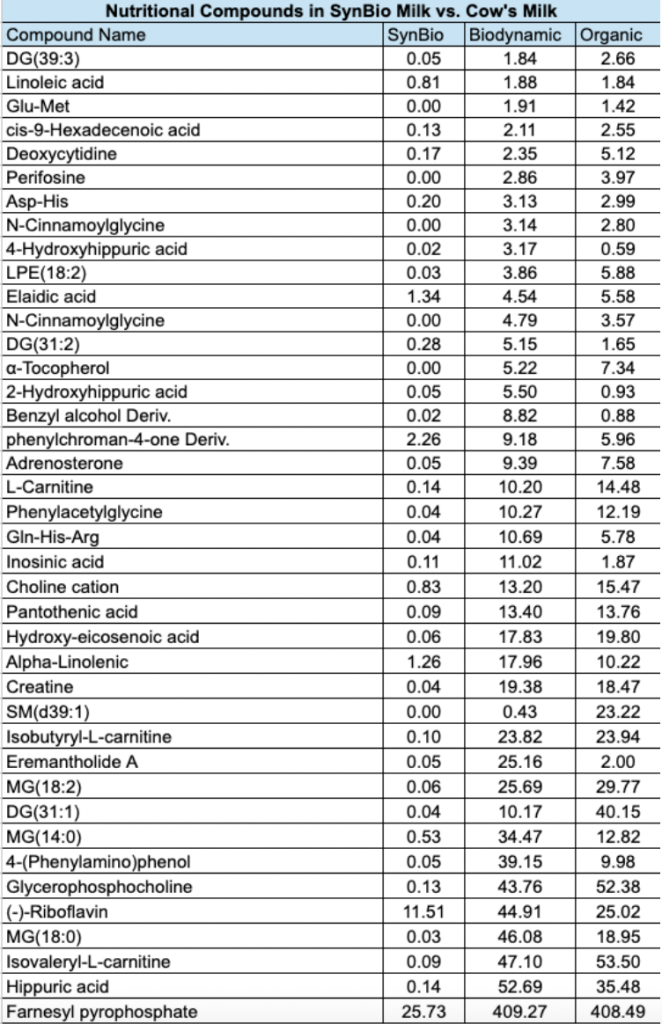

Further analysis showed that Perfect Day’s “milk” lacks critical nutrients found in real dairy, such as lipids, fatty acids, and intermediary metabolites. The product is not nutritionally equivalent to traditional milk, despite marketing claims to the contrary. We’ve raised similar concerns about synbio meat, which also lacks the full nutrient profile of real meat.

Conclusion: What’s at Stake?

Precision fermentation may be innovative, but innovation without transparency, oversight, or proven safety is a recipe for trouble. Don’t believe the hype about synbio foods as a sustainable solution to global challenges; we must recognize this as a potentially dangerous shift away from real, whole foods toward highly engineered, compositionally poorly characterized, minimally tested, substitutes.

Consumers deserve the right to know what they’re eating—and to choose whether or not they want synthetic biology on their plates. As the future of “ferming” unfolds, one thing is clear: this isn’t just about food. It’s about control, profit, regulation, and the fundamental nature and values that shape our food system.

Action Alert! Write to Congress and call for more testing for gene-edited and synbio foods. Please send your message immediately.

All genetically engineered crops should be removed from agriculture—they were never properly tested, and many scientists who did speak out prior to their approval were silenced or lost their jobs. Many health issues sky-rocketed during this era from leaky gut syndrome to faulty insulin regulation.