Miracle weight-loss injections like Ozempic promise an easy fix, but at what cost?

Listen to the audio version of this article:

THE TOPLINE

- GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro are being widely promoted as revolutionary weight-loss solutions, but their rapid adoption raises concerns about long-term safety, side effects, and pharmaceutical overreach.

- Reclassifying obesity as a “chronic disease” has opened the floodgates for drug marketing while sidelining proven, non-pharmaceutical nutrition and lifestyle interventions.

- Treating modifiable conditions with costly lifelong medications could create a generation of drug-dependent, physically frail patients while neglecting the root causes of metabolic health.

The excitement over new weight-loss injections like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro is sweeping headlines in both the US and UK. These GLP-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) drugs – or “skinny jabs” – originally developed for diabetes, are being forcefully promoted as game-changers for obesity and related diseases. Media outlets praise the drugs as ushering in a “golden age” of medicine, while social media influencers are aggressively advertising them to health-conscious consumers.

While it’s clear that many are experiencing stunning and rapid weight loss, it’s becoming ever more apparent that the side effects and potential risks associated with GLP-1 RA drugs are being downplayed. This is serious for several reasons, not least because patients are not afforded the right of informed consent, and, as a result, they don’t get to find out what alternatives are available that neither require lifelong dependence nor incur potential long-term risks.

Concerted efforts are underway to vastly expand the user base for these drugs. The Biden Administration tried to get GLP-1 RA drugs for obesity covered by Medicare, but the proposal was scrapped under the Trump Administration. (Note: Medicare covers GLP-1 RAs for diabetes and heart disease, and some state Medicaid programs cover them for obesity.) In the UK, experts are already calling for the National Health Service to accelerate use of GLP-1 jabs, citing research (funded by Novo Nordisk) that suggests the drugs lower short-term risks of heart attacks and strokes. These results are being used to push GLP-1 RAs to millions of people ostensibly to help them live longer…even if they are not obese.

Is Obesity a Disease?

Pharmaceutical enthusiasm is possible largely because, during the past decade, obesity has been recast not merely as a risk factor or lifestyle issue but as a chronic disease in its own right. The American Medical Association took that stance in 2013 and reaffirmed it in 2023. In an updated 2025 guidance, the FDA followed suit, changing its categorization of obesity from a “chronic, relapsing health risk” to a “chronic disease.”

Is this timing a coincidence with the rise of GLP-1 RAs? We think not. Categorization as a “disease” wraps a powerful regulatory ring-fence around obesity treatment. Once a condition sits inside that fence, only FDA-approved drugs may legally claim to treat, cure, prevent, or mitigate it; supplements, foods, and natural products are shut out. The same playbook was used when the FDA declared “inflammation” a disease years ago, clearing the competitive field for patented anti-inflammatories, and then in 2020 when the FDA saw fit to label “hangovers” a disease.

The numbers reveal what is at stake. Obesity’s classification as a disease paves the way for enormous pharmaceutical profits. Roughly 100 million American adults—about 40 percent of the population—are considered obese. Analysts foresee a $100 billion global market for obesity drugs by 2030, and as referenced above, we’re well on the way towards GLP-1 agonists being prescribed to virtually everyone for heart- or brain-health “maintenance.” From a business perspective it is Big Pharma’s wildest fever-dream: entire populations of drug-dependent patients on an injection for life.

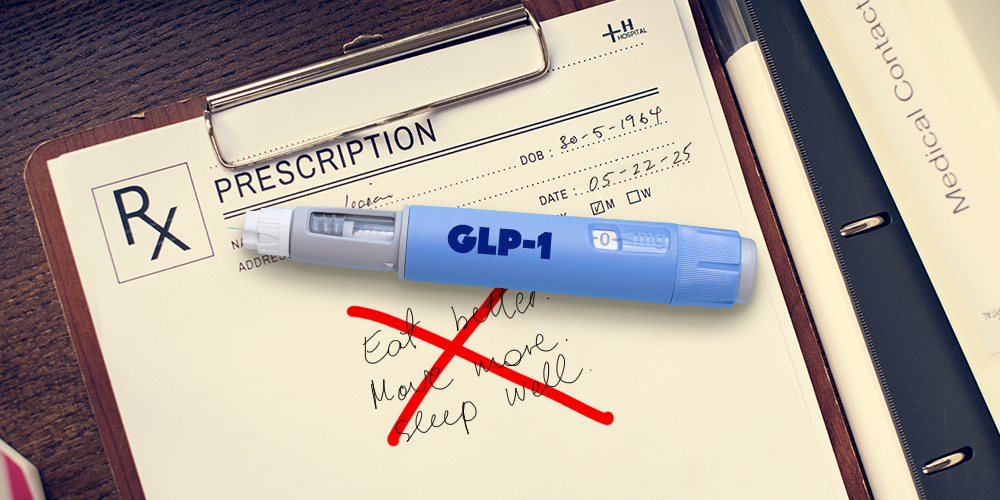

This framing of obesity as a disease fits seamlessly into the post–World War II medical paradigm—a worldview shaped by the promise of “a pill for every ill.” GLP-1 RAs, in many ways, are the apex of this mindset: a pharmaceutical solution to a condition rooted in complex social, behavioral, economic, and environmental factors. For decades, a healthcare system increasingly dominated by Big Pharma has trained us to believe that health is something delivered by a prescription pad rather than cultivated through our daily lives. We get sick, we go to the doctor, and we are handed a patented drug—often without serious discussion of the underlying issues making us sick.

In this model, downstream disease management consistently overshadows upstream prevention, despite overwhelming evidence that the foundations of true health lie in nutrition, movement, sleep, stress resilience, and meaningful social connection. By reclassifying obesity as a disease, we are turning what is often a modifiable condition into a lifelong diagnosis—and lifelong pharmaceutical dependence.

Prescribe Now, Ask Questions Later

These astounding developments raise serious questions. Are patients being fully informed of proven lifestyle approaches (diets, exercise, intermittent fasting) that can achieve similar metabolic benefits? Are patients made aware of the side effects of these medications? And what about long-term risks that only emerge after years?

While patients battling weight issues may welcome new options, it seems clear that the basic ethical tenet of informed consent is falling by the wayside. We fear that patients are not routinely being told about effective, non-drug alternatives – high-protein/high-fiber diets, regular exercise, or intermittent fasting – that can suppress appetite and improve insulin sensitivity naturally. Simply lowering body weight with a drug may feel easier than changing habits, but it does not build a foundation for long-term health.

Known and Emerging Risks of GLP-1 Drugs

Once drugs become FDA-approved, it’s taken as granted that they are “safe and effective.” Yet history counsels caution: many blockbusters once touted as “safe and effective” were later withdrawn for deadly side effects. In the early 2000s, Baycol (cerivastatin) — a best-selling cholesterol drug — was pulled after at least 52 patients died from muscle breakdown. Rezulin (troglitazone), a diabetes drug, was dropped in 2000 after cases of severe liver failure. There are many more examples. The point is that FDA approval isn’t a guarantee of long-term safety.

In fact, the warning labels on GLP-1 injections already list serious concerns. These drugs can cause pancreatitis and gallbladder disease, conditions tied to rapid weight loss and digestive slowdown. The Wegovy label explicitly warns clinicians that “acute pancreatitis… has been observed” and that gallbladder inflammation rates were higher in treated patients than controls. Case reports confirm that some patients have been hospitalized with life-threatening pancreatitis after weeks on Ozempic. Other known risks include nausea, vomiting and kidney injury (usually from dehydration) – the FDA notes cases of acute kidney failure sometimes requiring dialysis. Warnings also mention a theoretical risk of thyroid C-cell tumors: animal studies showed semaglutide causes thyroid cancer in rodents, so doctors must avoid GLP-1s in patients with a personal/family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma. (Whether this risk applies to humans is unknown.)

A particularly sensitive issue is mood and mental health: the Wegovy label advises doctors to watch for “the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts” and to avoid use in patients with active suicidal ideation. While large studies have had mixed findings, the FDA is reviewing anecdotal reports of severe mood changes in some users.

There’s also very real concern about GLP-1 RAs causing major loss of muscle mass, especially in older people who are already facing some degree of age-related muscle wasting (sarcopenia). This is likely an indirect effect of the drugs in which the body starts to use muscle tissue as a protein source given the energy deficit caused by the drugs’ effect on reducing food (energy) intake. Recent findings show that loss of lean body mass (muscle) can contribute to as much as 15-40% of the total weight lost. This loss of muscle tissue could be a major issue in terms of the available chemical energy (as adenosine triphosphate, ATP) that an individual needs to be able to run key processes in the body, including the immune system. It’s also concerning given we need sufficient muscle to avoid the complications typically associated with frailty, such as issues with bone health, posture, and risk of falls.

Other new concerns continue to emerge. A recent study found that GLP-1 RA users commonly fall short on vitamins and minerals because the drugs blunt appetite and speed gastric emptying. For example, patients on semaglutide may not absorb enough calcium, iron, or B12 because they eat less and their intestines work differently.

At over $1,000 per month retail, these are among the most expensive drugs on the market. Pushing Medicare/Medicaid coverage would channel billions of taxpayer dollars into Pharma coffers. Experts have warned that treating “everyone with obesity… with medications will bankrupt the country and still not cultivate the type of health and vitality we actually want.”

A Return to Upstream Health

True health often requires more than a pharmacy visit. Nutrition and lifestyle medicine experts emphasize whole-diet approaches (plenty of vegetables, fiber and protein), daily physical activity (including strength and endurance work), good sleep and stress reduction as the foundation for metabolic health. These strategies can raise natural GLP-1 levels and improve insulin sensitivity without the need for injections, along with other benefits like improved mood and muscle mass.

GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic and Wegovy definitely can offer benefits for some patients, but our concern is that the trade-offs are often glossed over. Before we write blanket prescriptions, we should insist on balanced information. Patients deserve to know about proven alternatives – intermittent fasting, low-carb nutrition, exercise – and about unanswered questions on long-term safety. Long-term health will come only from sustainable changes to lifestyle and environment – not just transferring body-fat onto a pharmaceutical tab.

Those who choose to use GLP-1 RAs should also know there are three things that can be very important accompaniments:

- Maintain a high protein diet (1.2-1.6 grams of pure protein per kilogram body mass; which equates to 5.4 to 7.3 grams (or one tenth to one quarter of an ounce) per 10 pounds body weight).

- Include 30 minutes of strength training in your activity schedule at least 3 times a week to try to offset some of the muscle loss.

- Consider using a body composition scale (e.g. by Tanita, Omron) to allow monitoring of body weight, alongside muscle mass, body fat percentage, visceral fat (fat around organs), bone mass, body water percentage, estimate of ‘metabolic’ age, etc.

Please share this article widely, especially among those who want more information about GLP-1 RA drugs.

I have been fat most of my adult life and I was not an overeater. I was, however, grossly hypothyroid, symptoms of which were ignored by every practitioner I saw until I was 54 years old by which time hypothyroidism had nearly killed me. I should point out that my “numbers” were always good and I was told I was fine despite terrible fatigue, painfully dry skin, very heavy periods. When you don’t properly treat hypothyroidism — and by that I mean natural desiccated thyroid, NOT levothyroxine — you can then prescribe antidepressants and every other drug known to humankind and make lots of money.

Obesity — every fat person hates that word and prefers FAT — is not a disease and about one-third of fat people are relatively healthy. Focusing on weight has been a godsend for lazy, incompetent medical personnel who are often fat themselves! And these newish drugs are a horror show. We live in a country where a large percentage of people are constipated and now we’re giving them drugs that paralyze their gut? Never mess with the gut, it is the foundation of all health as it houses the enteric nervous system which runs your heart, your immune system, etc. Pursue health not weight.